|

|

|

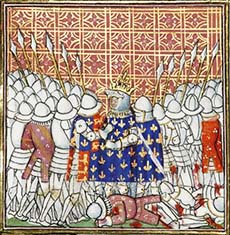

THE BATTLE OF POITIERS (September 19, 1356). In the early summer of 1356 the Black Prince took the field with a small army,

not more than from eight to ten thousand men,1 the most part not English, and rode into the Rouergue, Auvergne, and the Limousin, meeting

no resistance, sacking and taking all they found, and so upwards to the Loire.... The French King was lying before Breteuil, with a strong force,

when news of the Prince's northward ride came to him. He hastily granted the garrison of the town easy terms, and they withdrew to Cherbourg;

then he marched to Paris, and summoned all his nobles and fief-holders to a rendezvous on the borders of Blois and Touraine. He himself moved southwards

as far as Chartres.

The Black Prince threatened Bourges and Issoudun, failing to take either city; then he marched to Vierzon, a large town of no strength,

and took it; here he found, what he sorely needed, wine and food in plenty. While he lay here he heard that King John was at Chartres with all France at

his back, and that the passages of the Loire were occupied. So he broke up, and turned his face towards Bordeaux, at once abandoning any plan he may have

had of joining the Earl of Lancaster in Normandy. King John, hastening to overtake him, actually overshot the English army, and placed

himself across the Prince's line of retreat. Thus he had the English utterly in his power: a little patience and prudence, and he might have avenged

himself almost without loss on the invading army, by capturing both it and its brilliant captain. But, unfortunately for France, John 'the Good' was

possessed with chivalrous ideas, which prompted him to do exactly the wrong thing.

The Black Prince, seeing his retreat cut off, stood at bay in a strong position at Maupertuis, near Poitiers. It was a rough hill-side, covered with

vineyards; cut up by hedges, and also sprinkled with low scrub. Nothing could be better for defence: the chivalry of France, whose overwhelming weight

would have been irresistible on the plain, were of no avail on such a hillside; and there was plenty of cover to delight sharp-shooters who knew their

work. The only point of attack from the front was a narrow and hollow way, liable to a converging fire, which would grow more severe the farther the

enemy penetrated; for the cheeks of the ravine commanded the whole of the roadway.

On the level ground atop lay the main English force: every available point was crowded with archers; the narrow way had high hedge-crowned banks.

Underneath lay the 50,000 Frenchmen, 'the flower of their chivalry,' all feudal, no city-levies this time. The King was there, with his four sons,

his brother, and a crowd of great princes and barons. Had they been content to wait, and watch vigilantly, the Black Prince would have been starved,

and must have laid down his arms. This, however, was not their idea, nor the idea of that age. So they got them ready to assault the Prince's

formidable position; to give themselves the utmost disadvantage arising from useless numbers; and to give him the means of taking the greatest

possible advantage of his ground, where every man of his little force was available.

Before the assault took place the Papal Legate interposed, and obtained a truce for twenty-four hours. The Black Prince, knowing well his peril,

was willing to treat on terms honourable to France: unconditional surrender was the only thing King John would listen to. This would have been

as bad as a lost battle; what could they do but refuse? better die in arms than suffer imprisonment, starvation, and perhaps a shameful death.

So they set themselves to use the remainder of the day's truce in strengthening their position; an ambuscade was quietly posted on the left flank

of the one possible line of attack.

Next morning, the 19th of September, 1356, the French army was moved forwards: in the van came two marshals, Audenham and Clermont, with three

hundred men-at-arms, on swift warhorses; behind them were the Germans of Saarbrück and Nassau; then the Duke of Orleans in command of the

first line of battle; Charles, Duke of Normandy, the King's eldest son, was with the second; and lastly the King, surrounded by nineteen knights

all wearing his dress, that he might be the safer in the fight:2 before him fluttered the Oriflamme.

With heedless courage the vanguard dashed at the centre of the English position; for such were the King's orders. They rode full speed along the

narrow roadway up the hill-side, between the thick hedges; but the hill was steep, and the archers flanking it shot fast and well. A few only

struggled to the top; these were easily overthrown. The rest were rolled back in wild confusion on the Duke of Normandy's line, and broke their order;

at this moment the English ambuscade fell on their left flank. Then, when the "Black Prince saw that the Duke's battle 'was shaking and beginning

to open,' he bade his men mount quickly, and rode down into the midst, with loud cries of 'St. George' and 'Guienne.' Pushing on cheerily, he fell

upon the Constable of France, the Duke of Athens; the English archers, keeping pace afoot with the horsemen, supported them, shooting so swiftly

and well that the French and Germans were speedily put to flight.

With heedless courage the vanguard dashed at the centre of the English position; for such were the King's orders. They rode full speed along the

narrow roadway up the hill-side, between the thick hedges; but the hill was steep, and the archers flanking it shot fast and well. A few only

struggled to the top; these were easily overthrown. The rest were rolled back in wild confusion on the Duke of Normandy's line, and broke their order;

at this moment the English ambuscade fell on their left flank. Then, when the "Black Prince saw that the Duke's battle 'was shaking and beginning

to open,' he bade his men mount quickly, and rode down into the midst, with loud cries of 'St. George' and 'Guienne.' Pushing on cheerily, he fell

upon the Constable of France, the Duke of Athens; the English archers, keeping pace afoot with the horsemen, supported them, shooting so swiftly

and well that the French and Germans were speedily put to flight.

Then Charles, the Dauphin, with his two brothers, put spurs to their horses, and fled headlong from the field; there followed them full eight hundred

lances, the pride of the French army, who might well have upheld the fortune of the day. It was a pitiful beginning for the the young Prince,

who would so soon be called to fill his father's place. The first and second lines of battle were thus utterly scattered, almost in a moment:

some riding hither and thither off the field, in panic; others driven back under the walls of Poitiers, where the English garrison took great

store of negotiable prisoners; for at that time prisoners meant ransom.

The King, perhaps remembering the mishap of Crécy, now ordered all his line to dismount and fight afoot. And then for the first time

a stand was made, and something worthy of the name of a battle began. The French were still largely superior in force: at the beginning they

had been seven to one;3 and the advantage of the ground was no longer with the English. But the Prince of Wales pressed ever forwards,

with Sir John Chandos at his side, who bore himself so loyally that he never thought that day of prisoners, but kept on saying to the Prince

'Sire, ride onwards; God is with you, the day is yours!' 'And the Prince, who aimed at all perfectness of honour, rode onwards, with his banner

before him, succouring his people whenever he saw them scattering or unsteady, and proving himself a right good knight.4

The King, perhaps remembering the mishap of Crécy, now ordered all his line to dismount and fight afoot. And then for the first time

a stand was made, and something worthy of the name of a battle began. The French were still largely superior in force: at the beginning they

had been seven to one;3 and the advantage of the ground was no longer with the English. But the Prince of Wales pressed ever forwards,

with Sir John Chandos at his side, who bore himself so loyally that he never thought that day of prisoners, but kept on saying to the Prince

'Sire, ride onwards; God is with you, the day is yours!' 'And the Prince, who aimed at all perfectness of honour, rode onwards, with his banner

before him, succouring his people whenever he saw them scattering or unsteady, and proving himself a right good knight.4

Thus the English force fell, like an iron bar, on the soft mass of the French army, which had but little coherence, after the manner of a great

feudal levy; and this swift onset, with the Prince riding manfully in the van, like the point of the bar, scattered them hither and thither,

and decided the fortunes of the day. The Dukes of Bourbon and Athens perished, with many another of noble name; among them the Bishop of Chalons

in Champagne: the French gave back, till they were stayed by the walls of Poitiers. King John was now in the very thick of it: and with his own

hands did many feats of arms, defending himself manfully with a battle-axe.5 By his side was Philip, his youngest son, afterwards

Duke of Burgundy, founder of the second line of that house, who here earned for himself the name of 'le Hardi,' the Bold: for though but a child,

he stood gallantly by his father, warding off the blows that rained thickly on him.

The rout was too complete to be stayed by their gallantry. The gates of Poitiers were firmly shut; there was a great slaughter under the walls.

Round the King himself the fight was stubborn; many of his bodyguard were taken or slain. Geoffrey de Chargny, who bore the Oriflamme, went down:

and the King was hemmed in, all men being eager to take so great a prize. Through the crowd came shouldering a man of huge stature, Denis of Mortbeque,

a knight of St. Omer; when he got up to the King he prayed him in good French to surrender. The King then asked for 'his cousin, the Prince of Wales':

and Denis promised that if he would yield he would see him safely to the Prince: the King agreed. Thus he was taken, and with him Philip his little son.

The rout was too complete to be stayed by their gallantry. The gates of Poitiers were firmly shut; there was a great slaughter under the walls.

Round the King himself the fight was stubborn; many of his bodyguard were taken or slain. Geoffrey de Chargny, who bore the Oriflamme, went down:

and the King was hemmed in, all men being eager to take so great a prize. Through the crowd came shouldering a man of huge stature, Denis of Mortbeque,

a knight of St. Omer; when he got up to the King he prayed him in good French to surrender. The King then asked for 'his cousin, the Prince of Wales':

and Denis promised that if he would yield he would see him safely to the Prince: the King agreed. Thus he was taken, and with him Philip his little son.

Then arose around him a great debate between English and Gascons, all claiming to have taken him: they tore him away from Denis, and for a moment

he was in great peril. At last two barons, seeing the turmoil, rode up; and hearing that it was the French King, they spurred their horses,

forcing their way into the angry croud, and rescued him from their clutches. Then he was treated with high respect, and led to the Prince of Wales,

who bowed low to the ground before one who in the hierarchy of princes was his superior: he paid him all honour; sent for wine and spices, and served

them to him with his own hands. And thus King John, who one day before had held the English, as he thought, securely in his grasp, now found himself,

broken and wounded, a prisoner in their hands.

Thus went the great day of Maupertuis, or, as it is more commonly called by us, of Poitiers.

Great was the carnage among the French: they left eleven thousand on the field, of whom nearly two thousand five hundred6

were men of noble birth; while nearly a hundred barons, and full two thousand men-at-arms, to say nothing of lesser folk, were prisoners.

They were so many that the victors scarcely knew what to do with them: they fixed their ransom as quickly as they could, and then let them

go free on their word. The Prince with the huge booty gathered in his expedition, and with the richest prize of all, King John and his

little son, at once fell back to Bordeaux. The French army melted away like snow in spring, such feudal nobles as had escaped wandering

home crestfallen, the lawless and now lordless men-at-arms spreading over the land like a pestilence. A two-years' truce was struck between

England and France; and Edward at once carried his captives over to London.

1 Froissart (Buchon), xxiime addition 3, p. 155: 'Avec deux mille hommes d'armes et six mille archers, parmi les brigands' (i.e. besides the light-armed

mercenaries).

2 Froissart (Buchon), 3, c. 351, p. 186, 'armé lui vingtième de ses parements.'

3 Froissart (Buchon), 3, c. 360, p. 210, 'Les François étoient bien de gens d'armes sept contre un.'

4 Froissart (Buchon), 3, c. 361, p. 216.

5 Ibid. c. 364, p. 223.

6 In exact numbers, 2426. See the careful list given in Buchon's note to Froissart, 3, c. 364, p. 224.

Excerpted from:

Kitchin, G. W. A History of France, Vol 1, 3rd Ed, Rev.

Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1892. 437-444.

Other Local Resources:

Books for further study:

Allmand, Christopher. The Hundred Years War: England and France at War.

Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Barker, Juliet. Conquest: The English Kingdom of France, 1417-1450.

Harvard University Press, 2012.

Green, David. The Battle of Poitiers 1356.

Osprey Publishing, 2004.

Hoskins, Peter. In the Steps of the Black Prince: The Road to Poitiers, 1355-1356.

Boydell & Brewer, 2014.

Nicolle, David. Poitiers 1356: The Capture of a King.

The History Press, 2009.

Seward, Desmond. The Hundred Years War: The English in France 1337-1453.

Penguin, 1999.

The Battle of Poitiers on the Web:

| to Luminarium Encyclopedia |

Site ©1996-2023 Anniina Jokinen. All rights reserved.

This page was created on September 22, 2017. Last updated May 3, 2023.

|

Index of Encyclopedia Entries:

Medieval Cosmology

Prices of Items in Medieval England

Edward II

Isabella of France, Queen of England

Piers Gaveston

Thomas of Brotherton, E. of Norfolk

Edmund of Woodstock, E. of Kent

Thomas, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Lancaster, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster

Roger Mortimer, Earl of March

Hugh le Despenser the Younger

Bartholomew, Lord Burghersh, elder

Hundred Years' War (1337-1453)

Edward III

Philippa of Hainault, Queen of England

Edward, Black Prince of Wales

John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall

The Battle of Crécy, 1346

The Siege of Calais, 1346-7

The Battle of Poitiers, 1356

Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York

Thomas of Woodstock, Gloucester

Richard of York, E. of Cambridge

Richard Fitzalan, 3. Earl of Arundel

Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March

The Good Parliament, 1376

Richard II

The Peasants' Revolt, 1381

Lords Appellant, 1388

Richard Fitzalan, 4. Earl of Arundel

Archbishop Thomas Arundel

Thomas de Beauchamp, E. Warwick

Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford

Ralph Neville, E. of Westmorland

Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk

Edmund Mortimer, 3. Earl of March

Roger Mortimer, 4. Earl of March

John Holland, Duke of Exeter

Michael de la Pole, E. Suffolk

Hugh de Stafford, 2. E. Stafford

Henry IV

Edward, Duke of York

Edmund Mortimer, 5. Earl of March

Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland

Sir Henry Percy, "Harry Hotspur"

Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester

Owen Glendower

The Battle of Shrewsbury, 1403

Archbishop Richard Scrope

Thomas Mowbray, 3. E. Nottingham

John Mowbray, 2. Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Fitzalan, 5. Earl of Arundel

Henry V

Thomas, Duke of Clarence

John, Duke of Bedford

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury

Richard, Earl of Cambridge

Henry, Baron Scrope of Masham

William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Montacute, E. Salisbury

Richard Beauchamp, E. of Warwick

Henry Beauchamp, Duke of Warwick

Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter

Cardinal Henry Beaufort

John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset

Sir John Fastolf

John Holland, 2. Duke of Exeter

Archbishop John Stafford

Archbishop John Kemp

Catherine of Valois

Owen Tudor

John Fitzalan, 7. Earl of Arundel

John, Lord Tiptoft

Charles VII, King of France

Joan of Arc

Louis XI, King of France

Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy

The Battle of Agincourt, 1415

The Battle of Castillon, 1453

The Wars of the Roses 1455-1485

Causes of the Wars of the Roses

The House of Lancaster

The House of York

The House of Beaufort

The House of Neville

The First Battle of St. Albans, 1455

The Battle of Blore Heath, 1459

The Rout of Ludford, 1459

The Battle of Northampton, 1460

The Battle of Wakefield, 1460

The Battle of Mortimer's Cross, 1461

The 2nd Battle of St. Albans, 1461

The Battle of Towton, 1461

The Battle of Hedgeley Moor, 1464

The Battle of Hexham, 1464

The Battle of Edgecote, 1469

The Battle of Losecoat Field, 1470

The Battle of Barnet, 1471

The Battle of Tewkesbury, 1471

The Treaty of Pecquigny, 1475

The Battle of Bosworth Field, 1485

The Battle of Stoke Field, 1487

Henry VI

Margaret of Anjou

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York

Edward IV

Elizabeth Woodville

Richard Woodville, 1. Earl Rivers

Anthony Woodville, 2. Earl Rivers

Jane Shore

Edward V

Richard III

George, Duke of Clarence

Ralph Neville, 2. Earl of Westmorland

Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick

Edward Neville, Baron Bergavenny

William Neville, Lord Fauconberg

Robert Neville, Bishop of Salisbury

John Neville, Marquis of Montagu

George Neville, Archbishop of York

John Beaufort, 1. Duke Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 2. Duke Somerset

Henry Beaufort, 3. Duke of Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 4. Duke Somerset

Margaret Beaufort

Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond

Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke

Humphrey Stafford, D. Buckingham

Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham

Humphrey Stafford, E. of Devon

Thomas, Lord Stanley, Earl of Derby

Sir William Stanley

Archbishop Thomas Bourchier

Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex

John Mowbray, 3. Duke of Norfolk

John Mowbray, 4. Duke of Norfolk

John Howard, Duke of Norfolk

Henry Percy, 2. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 3. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 4. E. Northumberland

William, Lord Hastings

Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter

William Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford

Thomas de Clifford, 8. Baron Clifford

John de Clifford, 9. Baron Clifford

John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester

Thomas Grey, 1. Marquis Dorset

Sir Andrew Trollop

Archbishop John Morton

Edward Plantagenet, E. of Warwick

John Talbot, 2. E. Shrewsbury

John Talbot, 3. E. Shrewsbury

John de la Pole, 2. Duke of Suffolk

John de la Pole, E. of Lincoln

Edmund de la Pole, E. of Suffolk

Richard de la Pole

John Sutton, Baron Dudley

James Butler, 5. Earl of Ormonde

Sir James Tyrell

Edmund Grey, first Earl of Kent

George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent

John, 5th Baron Scrope of Bolton

James Touchet, 7th Baron Audley

Walter Blount, Lord Mountjoy

Robert Hungerford, Lord Moleyns

Thomas, Lord Scales

John, Lord Lovel and Holand

Francis Lovell, Viscount Lovell

Sir Richard Ratcliffe

William Catesby

Ralph, 4th Lord Cromwell

Jack Cade's Rebellion, 1450

Tudor Period

King Henry VII

Queen Elizabeth of York

Arthur, Prince of Wales

Lambert Simnel

Perkin Warbeck

The Battle of Blackheath, 1497

King Ferdinand II of Aragon

Queen Isabella of Castile

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

King Henry VIII

Queen Catherine of Aragon

Queen Anne Boleyn

Queen Jane Seymour

Queen Anne of Cleves

Queen Catherine Howard

Queen Katherine Parr

King Edward VI

Queen Mary I

Queen Elizabeth I

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond

Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland

James IV, King of Scotland

The Battle of Flodden Field, 1513

James V, King of Scotland

Mary of Guise, Queen of Scotland

Mary Tudor, Queen of France

Louis XII, King of France

Francis I, King of France

The Battle of the Spurs, 1513

Field of the Cloth of Gold, 1520

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Ambassador

The Siege of Boulogne, 1544

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex

Thomas, Lord Audley

Thomas Wriothesley, E. Southampton

Sir Richard Rich

Edward Stafford, D. of Buckingham

Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire

George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford

John Russell, Earl of Bedford

Thomas Grey, 2. Marquis of Dorset

Henry Grey, D. of Suffolk

Charles Somerset, Earl of Worcester

George Talbot, 4. E. Shrewsbury

Francis Talbot, 5. E. Shrewsbury

Henry Algernon Percy,

5th Earl of Northumberland

Henry Algernon Percy,

6th Earl of Northumberland

Ralph Neville, 4. E. Westmorland

Henry Neville, 5. E. Westmorland

William Paulet, Marquis of Winchester

Sir Francis Bryan

Sir Nicholas Carew

John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford

Thomas Seymour, Lord Admiral

Edward Seymour, Protector Somerset

Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury

Henry Pole, Lord Montague

Sir Geoffrey Pole

Thomas Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Bourchier, 2. Earl of Essex

Robert Radcliffe, 1. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 2. Earl of Sussex

George Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon

Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter

George Neville, Baron Bergavenny

Sir Edward Neville

William, Lord Paget

William Sandys, Baron Sandys

William Fitzwilliam, E. Southampton

Sir Anthony Browne

Sir Thomas Wriothesley

Sir William Kingston

George Brooke, Lord Cobham

Sir Richard Southwell

Thomas Fiennes, 9th Lord Dacre

Sir Francis Weston

Henry Norris

Lady Jane Grey

Sir Thomas Arundel

Sir Richard Sackville

Sir William Petre

Sir John Cheke

Walter Haddon, L.L.D

Sir Peter Carew

Sir John Mason

Nicholas Wotton

John Taylor

Sir Thomas Wyatt, the Younger

Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio

Cardinal Reginald Pole

Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester

Edmund Bonner, Bishop of London

Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London

John Hooper, Bishop of Gloucester

John Aylmer, Bishop of London

Thomas Linacre

William Grocyn

Archbishop William Warham

Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of Durham

Richard Fox, Bishop of Winchester

Edward Fox, Bishop of Hereford

Pope Julius II

Pope Leo X

Pope Clement VII

Pope Paul III

Pope Pius V

Pico della Mirandola

Desiderius Erasmus

Martin Bucer

Richard Pace

Christopher Saint-German

Thomas Tallis

Elizabeth Barton, the Nun of Kent

Hans Holbein, the Younger

The Sweating Sickness

Dissolution of the Monasteries

Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536

Robert Aske

Anne Askew

Lord Thomas Darcy

Sir Robert Constable

Oath of Supremacy

The Act of Supremacy, 1534

The First Act of Succession, 1534

The Third Act of Succession, 1544

The Ten Articles, 1536

The Six Articles, 1539

The Second Statute of Repeal, 1555

The Act of Supremacy, 1559

Articles Touching Preachers, 1583

Queen Elizabeth I

William Cecil, Lord Burghley

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury

Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Nicholas Bacon

Sir Thomas Bromley

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Ambrose Dudley, Earl of Warwick

Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon

Sir Thomas Egerton, Viscount Brackley

Sir Francis Knollys

Katherine "Kat" Ashley

Lettice Knollys, Countess of Leicester

George Talbot, 6. E. of Shrewsbury

Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury

Gilbert Talbot, 7. E. of Shrewsbury

Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Robert Sidney

Archbishop Matthew Parker

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Penelope Devereux, Lady Rich

Sir Christopher Hatton

Edward Courtenay, E. Devonshire

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Thomas Radcliffe, 3. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 4. Earl of Sussex

Robert Radcliffe, 5. Earl of Sussex

William Parr, Marquis of Northampton

Henry Wriothesley, 2. Southampton

Henry Wriothesley, 3. Southampton

Charles Neville, 6. E. Westmorland

Thomas Percy, 7. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 8. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 9. E. Nothumberland

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

Charles, Lord Howard of Effingham

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk

Henry Howard, 1. Earl of Northampton

Thomas Howard, 1. Earl of Suffolk

Henry Hastings, 3. E. of Huntingdon

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland

Francis Manners, 6th Earl of Rutland

Henry FitzAlan, 12. Earl of Arundel

Thomas, Earl Arundell of Wardour

Edward Somerset, E. of Worcester

William Davison

Sir Walter Mildmay

Sir Ralph Sadler

Sir Amyas Paulet

Gilbert Gifford

Anthony Browne, Viscount Montague

François, Duke of Alençon & Anjou

Mary, Queen of Scots

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell

Anthony Babington and the Babington Plot

John Knox

Philip II of Spain

The Spanish Armada, 1588

Sir Francis Drake

Sir John Hawkins

William Camden

Archbishop Whitgift

Martin Marprelate Controversy

John Penry (Martin Marprelate)

Richard Bancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury

John Dee, Alchemist

Philip Henslowe

Edward Alleyn

The Blackfriars Theatre

The Fortune Theatre

The Rose Theatre

The Swan Theatre

Children's Companies

The Admiral's Men

The Lord Chamberlain's Men

Citizen Comedy

The Isle of Dogs, 1597

Common Law

Court of Common Pleas

Court of King's Bench

Court of Star Chamber

Council of the North

Fleet Prison

Assize

Attainder

First Fruits & Tenths

Livery and Maintenance

Oyer and terminer

Praemunire

The Stuarts

King James I of England

Anne of Denmark

Henry, Prince of Wales

The Gunpowder Plot, 1605

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset

Arabella Stuart, Lady Lennox

William Alabaster

Bishop Hall

Bishop Thomas Morton

Archbishop William Laud

John Selden

Lucy Harington, Countess of Bedford

Henry Lawes

King Charles I

Queen Henrietta Maria

Long Parliament

Rump Parliament

Kentish Petition, 1642

Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford

John Digby, Earl of Bristol

George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax

Robert Devereux, 3rd E. of Essex

Robert Sidney, 2. E. of Leicester

Algernon Percy, E. of Northumberland

Henry Montagu, Earl of Manchester

Edward Montagu, 2. Earl of Manchester

The Restoration

King Charles II

King James II

Test Acts

Greenwich Palace

Hatfield House

Richmond Palace

Windsor Palace

Woodstock Manor

The Cinque Ports

Mermaid Tavern

Malmsey Wine

Great Fire of London, 1666

Merchant Taylors' School

Westminster School

The Sanctuary at Westminster

"Sanctuary"

Images:

Chart of the English Succession from William I through Henry VII

Medieval English Drama

London c1480, MS Royal 16

London, 1510, the earliest view in print

Map of England from Saxton's Descriptio Angliae, 1579

London in late 16th century

Location Map of Elizabethan London

Plan of the Bankside, Southwark, in Shakespeare's time

Detail of Norden's Map of the Bankside, 1593

Bull and Bear Baiting Rings from the Agas Map (1569-1590, pub. 1631)

Sketch of the Swan Theatre, c. 1596

Westminster in the Seventeenth Century, by Hollar

Visscher's View of London, 1616

Larger Visscher's View in Sections

c. 1690. View of London Churches, after the Great Fire

The Yard of the Tabard Inn from Thornbury, Old and New London

|

|