|

|

|

ANNE ASKEW (1521-1546), protestant martyr, was the second daughter of Sir William Askew, or Ayscough, knight, who is

generally stated to be of Kelsey in Lincolnshire. But according to family and local tradition she was born at Stallingborough,

near Grimsby, where the site of her father's house is still pointed out.1 The Askews were an old Lincolnshire family,

and the consciousness of this fact may have had something to do with the formation of Anne's character. She was highly educated

and much devoted to biblical study. When she stayed at Lincoln she was seen daily in the cathedral reading the Bible, and engaging

the clergy in discussions on the meaning of particular texts. According to her own account she was superior to them all in argument,

and those who wished to answer her commonly retired without a word.

At a time when she was probably still a girl a marriage was arranged by her parents for her elder sister, who was to be the wife

of one Thomas Kyme of Kelsey. It was one of those feudal bargains which were of constant occurrence in the domestic life of those

days. But the intended bride died before it was fulfilled, and her father, 'to save the money,' as we are expressly told, caused

Anne to supply her place against her own will. She accordingly married Kyme, and had two children by him. But having, as it is

said, offended the priests, her husband put her out of his house, on which she, for her part, was glad to leave him, and was

supposed to have sought a divorce. Whether it was with this view that she came to London does not appear; but in March 1545 she

underwent some examinations for heresy, of which she herself has left us an account, first at Sadler's Hall2 by one

Christopher Dare, then before the lord mayor of London, who committed her to the Counter,3 and afterwards before

Bishop Bonner and a number of other divines. It is unfortunate that we have no other record of these

proceedings than her own,4 which though honest was undoubtedly one-sided, and is not likely to have been improved in the

direction of impartiality by having been first edited by John Bale,

afterwards bishop of Ossory, during his exile in Germany.

The subject on which she lay under suspicion of heresy was the sacrament. The severe Act of the Six Articles,

passed some years before, had produced such a crop of ecclesiastical prosecutions that parliament had been already obliged to

restrict its operation by another statute, and Henry VIII himself at

the end of this very year thought it well to deliver an exhortation to parliament on the subject of christian charity. In such

a state of matters Anne Askew had little chance of mercy. It is, however, tolerably clear, notwithstanding the gloss which

Bale, and Fox

after him, endeavoured to put upon it, that one man who sincerely tried to befriend her was the much-abused

Bishop Bonner. He did his utmost to conquer her distrust and get her to talk with him familiarly,

promising that no advantage should be taken of unwary words; and he actually succeeded in extracting from her a perfectly orthodox

confession (according to the standard then acknowledged), with which he sought to protect her from further molestation. But when it

was read over to her, and she was asked to sign, although she had acknowledged every word of it before, instead of her simple

signature she added, 'I, Anne Askew, do believe all manner of things contained in the faith of the Catholic Church, and not

otherwise.' The bishop was quite disconcerted. In Anne's own words, 'he flung into his chamber in a great fury.' He had told her

that she might thank others, and not herself, for the favour he had shown her, as she was so well connected. Now she seemed anxious

to undo all his efforts on her behalf. Dr. Weston, however (afterwards Queen Mary's dean of Westminster),

contrived at this point to save her from her own indiscretion, representing to the bishop that she had not taken sufficient notice

of the reference actually made to the church in the written form of the confession, and thought she was supplying an omission. The

bishop was accordingly persuaded to come out again, and after some further explanations Anne was at length liberated upon sureties

for her forthcoming whenever she should be further called in question. She had still to appear before the lord mayor, and did so on

13 June following, when she and two other persons, one being of her own sex, were arraigned under the act as sacramentaries; but no

witnesses appeared against her or either of the others, except one against the man, and they were all three acquitted and set at

liberty.

The accusers of Anne had for the time been put to silence, but unfortunately within a year new grounds of complaint were urged, and

she was examined a second time before the council at Greenwich. Her opinions meanwhile seem to have been growing more decidedly

heretical, and her old assurance in the face of learned disputants was stronger than ever. She was first asked some questions about

her husband, and refused to reply except before the king himself. She was then asked her opinion of the sacrament, and, being

admonished to speak directly to the point, said she would not sing a new song of the Lord in a strange land. Bishop Gardiner

told her she spoke in parables. She replied that it was best for him, for if she showed him the open truth he would not accept it.

He then told her that she was a parrot, and she declared herself ready to suffer not only rebuke but everything else at his hands.

She had an answer ready for each of the council that examined her. Indeed, she sometimes seemed to be examining them, for she asked

the lord chancellor himself how long he would halt on both sides.

Nevertheless, she was more closely questioned this time than she had been the year before. She was five hours before the council at

Greenwich, and was examined again on the following day, being meantime conveyed to Lady Garnish.5 On the following Sunday

she was very ill and desired to speak with Latimer, but was not allowed,

let in the extremity of her illness she was sent to Newgate in such pain as she had never suffered in her

life. But worse awaited her. On Tuesday following she was conveyed from Newgate to the sign of the Crown, where

Sir Richard Rich endeavoured to persuade her to abandon her heresy. Dr. Shaxton, also, late bishop of

Salisbury, urged her to make a recantation, as he had just lately done himself, but all to no purpose. Rich accordingly sent her to

the Tower, where a new set of inquiries were addressed to her, for it seems some members of the council suspected that she received

secret encouragement from persons of great influence. She denied, however, that she knew any man or woman of her sect, and explained

that during her last year's imprisonment in the Counter she had been maintained by the efforts of her maid, who 'made moan' for her

to the prentices in the street, and collected money from them. She did not know the name of any one who had given her money, but

acknowledged that a man in a blue coat had given her ten shillings, and said it was from my lady Hertford. More than this even the

rack could not get from her, which by her own statement afterwards (if we may trust a narrative which could scarcely in such a case

have been actually penned by herself) was applied by Lord Chancellor Wriothesley himself and

Sir Richard Rich, turning the screws with their own hands. Yet even after being released from this

torture she 'sat two long hours reasoning with my lord chancellor upon the bare floor,' but could not be induced to change her opinion.

So far we have followed the account given as that of the sufferer herself. But it should be noticed that on 18 June 1546 she was

arraigned for heresy at the Guildhall along with Dr. Shaxton and two others, all of whom confessed the indictment, and were sentenced

to the fire. Dr. Shaxton and one of the others recanted next day, and it was either that day or a few days later that Anne Askew was

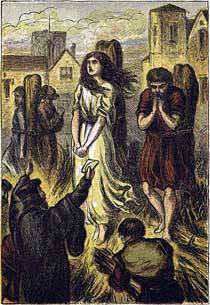

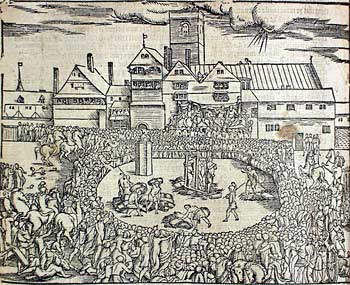

racked in the Tower. On 16 July she and three others guilty of the same heresy were brought to the stake in Smithfield, she being so

weak from the torture she had already undergone that she had to be carried in a chair.6 She was tied to the stake by a chain

round the waist which supported her body. On a bench under St. Bartholomew's Church sat Lord Chancellor Wriothesley,

the Dukes of Norfolk and Bedford,

the lord mayor, and others, to witness the shameful tragedy; and, to complete the matter, Dr. Shaxton, who had so recently recanted the

same heresy, was appointed to preach to the victims. Anne still preserved her marvellous self-possession, and made passing comments on

the preacher's words, confirming them where she agreed with him, and at other times saying 'There he misseth and speaketh without the

book.' After the sermon the martyrs began to pray. The titled spectators on the bench were more discomposed, knowing that there was some

gunpowder near the faggots, which they feared might send them flying about their ears. But the Earl of Bedford

reassured them. The gunpowder was not under the faggots, but laid about the bodies of the victims to rid them the sooner of their pain.

Finally Lord Chancellor Wriothesley sent Anne Askew letters with an assurance of the king's pardon if she would even now recant. She

refused to look at them, saying she came not thither to deny her Master. A like refusal was made by the other sufferers. The lord mayor

then cried out 'Fiat justitia!' and ordered the fire to be laid to the faggots. Soon afterwards all was over.7

Anne is said by Bale to have been twenty-five years old when she suffered.

She must therefore have been born in the year 1521.

There cannot be a doubt that the memory of this woman's sufferings and of her extraordinary fortitude and heroism added

strength to the protestant reaction under Edward VI. The account of her martyrdom published by

Bale in Germany, Strype tells us, was publicly exposed to sale at Winchester in

1549, in reproach of Bishop Gardiner, who was believed (whether justly or not is another question) to have been

a great cause of her death. 'Four of these books,' says Strype, 'came to that bishop's own eyes, being then at Winchester; they had leaves

put in as additions to the book, some glued and some unglued, which probably contained some further intelligences that the author had gathered

since his first writing of the book. And herein some reflections were made freely, according to Bale's talent, upon some of the court, not

sparing Paget himself, though then secretary of state.'8 We ought certainly to make some allowance for

bias in testimony that could be manipulated after such a fashion, but we need not be sparing in sympathy for the devoted sufferer.

— James Gairdner.

[AJ Notes:]

1. It is to be noted that Gairdner's article was written in 1885; whether the house's location is still commonly pointed out is not known to this editor.

2. Saddler's Hall was the guildhall of the Saddle-makers' Guild.

3. The Counter Prison, or the Compter, was located in Bread Street until 1555.

4. See: The First Examination of Anne Askew from Foxe's Book of Martyrs.

5. Prison.

6. Gairdner here supposes Askew merely weak; if she was racked, chances are her legs and arms had been dislocated and pulled out of their sockets, making standing or walking impossible.

7. See: The Death of Anne Askew from Foxe's Book of Martyrs.

8. Memorials of Cranmer, 294.

Source:

Gairdner, James. "Anne Askew."

The Dictionary of National Biography. Vol II. Leslie Stephen, Ed.

London: Smith, Elder, & Co., 1885. 190-192.

Other Local Resources:

Books for further study:

Beilin, Elaine V., ed. The Examinations of Anne Askew.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Zahl, Paul F. M. Five Women of the English Reformation.

Cambridge: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2001.

Web Links:

| to Luminarium Encyclopedia |

Site ©1996-2023 Anniina Jokinen. All rights reserved.

This page was created on July 16, 2010. Last updated February 25, 2023.

|

Index of Encyclopedia Entries:

Medieval Cosmology

Prices of Items in Medieval England

Edward II

Isabella of France, Queen of England

Piers Gaveston

Thomas of Brotherton, E. of Norfolk

Edmund of Woodstock, E. of Kent

Thomas, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Lancaster, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster

Roger Mortimer, Earl of March

Hugh le Despenser the Younger

Bartholomew, Lord Burghersh, elder

Hundred Years' War (1337-1453)

Edward III

Philippa of Hainault, Queen of England

Edward, Black Prince of Wales

John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall

The Battle of Crécy, 1346

The Siege of Calais, 1346-7

The Battle of Poitiers, 1356

Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York

Thomas of Woodstock, Gloucester

Richard of York, E. of Cambridge

Richard Fitzalan, 3. Earl of Arundel

Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March

The Good Parliament, 1376

Richard II

The Peasants' Revolt, 1381

Lords Appellant, 1388

Richard Fitzalan, 4. Earl of Arundel

Archbishop Thomas Arundel

Thomas de Beauchamp, E. Warwick

Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford

Ralph Neville, E. of Westmorland

Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk

Edmund Mortimer, 3. Earl of March

Roger Mortimer, 4. Earl of March

John Holland, Duke of Exeter

Michael de la Pole, E. Suffolk

Hugh de Stafford, 2. E. Stafford

Henry IV

Edward, Duke of York

Edmund Mortimer, 5. Earl of March

Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland

Sir Henry Percy, "Harry Hotspur"

Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester

Owen Glendower

The Battle of Shrewsbury, 1403

Archbishop Richard Scrope

Thomas Mowbray, 3. E. Nottingham

John Mowbray, 2. Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Fitzalan, 5. Earl of Arundel

Henry V

Thomas, Duke of Clarence

John, Duke of Bedford

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury

Richard, Earl of Cambridge

Henry, Baron Scrope of Masham

William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Montacute, E. Salisbury

Richard Beauchamp, E. of Warwick

Henry Beauchamp, Duke of Warwick

Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter

Cardinal Henry Beaufort

John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset

Sir John Fastolf

John Holland, 2. Duke of Exeter

Archbishop John Stafford

Archbishop John Kemp

Catherine of Valois

Owen Tudor

John Fitzalan, 7. Earl of Arundel

John, Lord Tiptoft

Charles VII, King of France

Joan of Arc

Louis XI, King of France

Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy

The Battle of Agincourt, 1415

The Battle of Castillon, 1453

The Wars of the Roses 1455-1485

Causes of the Wars of the Roses

The House of Lancaster

The House of York

The House of Beaufort

The House of Neville

The First Battle of St. Albans, 1455

The Battle of Blore Heath, 1459

The Rout of Ludford, 1459

The Battle of Northampton, 1460

The Battle of Wakefield, 1460

The Battle of Mortimer's Cross, 1461

The 2nd Battle of St. Albans, 1461

The Battle of Towton, 1461

The Battle of Hedgeley Moor, 1464

The Battle of Hexham, 1464

The Battle of Edgecote, 1469

The Battle of Losecoat Field, 1470

The Battle of Barnet, 1471

The Battle of Tewkesbury, 1471

The Treaty of Pecquigny, 1475

The Battle of Bosworth Field, 1485

The Battle of Stoke Field, 1487

Henry VI

Margaret of Anjou

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York

Edward IV

Elizabeth Woodville

Richard Woodville, 1. Earl Rivers

Anthony Woodville, 2. Earl Rivers

Jane Shore

Edward V

Richard III

George, Duke of Clarence

Ralph Neville, 2. Earl of Westmorland

Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick

Edward Neville, Baron Bergavenny

William Neville, Lord Fauconberg

Robert Neville, Bishop of Salisbury

John Neville, Marquis of Montagu

George Neville, Archbishop of York

John Beaufort, 1. Duke Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 2. Duke Somerset

Henry Beaufort, 3. Duke of Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 4. Duke Somerset

Margaret Beaufort

Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond

Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke

Humphrey Stafford, D. Buckingham

Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham

Humphrey Stafford, E. of Devon

Thomas, Lord Stanley, Earl of Derby

Sir William Stanley

Archbishop Thomas Bourchier

Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex

John Mowbray, 3. Duke of Norfolk

John Mowbray, 4. Duke of Norfolk

John Howard, Duke of Norfolk

Henry Percy, 2. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 3. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 4. E. Northumberland

William, Lord Hastings

Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter

William Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford

Thomas de Clifford, 8. Baron Clifford

John de Clifford, 9. Baron Clifford

John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester

Thomas Grey, 1. Marquis Dorset

Sir Andrew Trollop

Archbishop John Morton

Edward Plantagenet, E. of Warwick

John Talbot, 2. E. Shrewsbury

John Talbot, 3. E. Shrewsbury

John de la Pole, 2. Duke of Suffolk

John de la Pole, E. of Lincoln

Edmund de la Pole, E. of Suffolk

Richard de la Pole

John Sutton, Baron Dudley

James Butler, 5. Earl of Ormonde

Sir James Tyrell

Edmund Grey, first Earl of Kent

George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent

John, 5th Baron Scrope of Bolton

James Touchet, 7th Baron Audley

Walter Blount, Lord Mountjoy

Robert Hungerford, Lord Moleyns

Thomas, Lord Scales

John, Lord Lovel and Holand

Francis Lovell, Viscount Lovell

Sir Richard Ratcliffe

William Catesby

Ralph, 4th Lord Cromwell

Jack Cade's Rebellion, 1450

Tudor Period

King Henry VII

Queen Elizabeth of York

Arthur, Prince of Wales

Lambert Simnel

Perkin Warbeck

The Battle of Blackheath, 1497

King Ferdinand II of Aragon

Queen Isabella of Castile

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

King Henry VIII

Queen Catherine of Aragon

Queen Anne Boleyn

Queen Jane Seymour

Queen Anne of Cleves

Queen Catherine Howard

Queen Katherine Parr

King Edward VI

Queen Mary I

Queen Elizabeth I

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond

Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland

James IV, King of Scotland

The Battle of Flodden Field, 1513

James V, King of Scotland

Mary of Guise, Queen of Scotland

Mary Tudor, Queen of France

Louis XII, King of France

Francis I, King of France

The Battle of the Spurs, 1513

Field of the Cloth of Gold, 1520

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Ambassador

The Siege of Boulogne, 1544

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex

Thomas, Lord Audley

Thomas Wriothesley, E. Southampton

Sir Richard Rich

Edward Stafford, D. of Buckingham

Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire

George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford

John Russell, Earl of Bedford

Thomas Grey, 2. Marquis of Dorset

Henry Grey, D. of Suffolk

Charles Somerset, Earl of Worcester

George Talbot, 4. E. Shrewsbury

Francis Talbot, 5. E. Shrewsbury

Henry Algernon Percy,

5th Earl of Northumberland

Henry Algernon Percy,

6th Earl of Northumberland

Ralph Neville, 4. E. Westmorland

Henry Neville, 5. E. Westmorland

William Paulet, Marquis of Winchester

Sir Francis Bryan

Sir Nicholas Carew

John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford

Thomas Seymour, Lord Admiral

Edward Seymour, Protector Somerset

Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury

Henry Pole, Lord Montague

Sir Geoffrey Pole

Thomas Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Bourchier, 2. Earl of Essex

Robert Radcliffe, 1. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 2. Earl of Sussex

George Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon

Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter

George Neville, Baron Bergavenny

Sir Edward Neville

William, Lord Paget

William Sandys, Baron Sandys

William Fitzwilliam, E. Southampton

Sir Anthony Browne

Sir Thomas Wriothesley

Sir William Kingston

George Brooke, Lord Cobham

Sir Richard Southwell

Thomas Fiennes, 9th Lord Dacre

Sir Francis Weston

Henry Norris

Lady Jane Grey

Sir Thomas Arundel

Sir Richard Sackville

Sir William Petre

Sir John Cheke

Walter Haddon, L.L.D

Sir Peter Carew

Sir John Mason

Nicholas Wotton

John Taylor

Sir Thomas Wyatt, the Younger

Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio

Cardinal Reginald Pole

Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester

Edmund Bonner, Bishop of London

Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London

John Hooper, Bishop of Gloucester

John Aylmer, Bishop of London

Thomas Linacre

William Grocyn

Archbishop William Warham

Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of Durham

Richard Fox, Bishop of Winchester

Edward Fox, Bishop of Hereford

Pope Julius II

Pope Leo X

Pope Clement VII

Pope Paul III

Pope Pius V

Pico della Mirandola

Desiderius Erasmus

Martin Bucer

Richard Pace

Christopher Saint-German

Thomas Tallis

Elizabeth Barton, the Nun of Kent

Hans Holbein, the Younger

The Sweating Sickness

Dissolution of the Monasteries

Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536

Robert Aske

Anne Askew

Lord Thomas Darcy

Sir Robert Constable

Oath of Supremacy

The Act of Supremacy, 1534

The First Act of Succession, 1534

The Third Act of Succession, 1544

The Ten Articles, 1536

The Six Articles, 1539

The Second Statute of Repeal, 1555

The Act of Supremacy, 1559

Articles Touching Preachers, 1583

Queen Elizabeth I

William Cecil, Lord Burghley

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury

Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Nicholas Bacon

Sir Thomas Bromley

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Ambrose Dudley, Earl of Warwick

Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon

Sir Thomas Egerton, Viscount Brackley

Sir Francis Knollys

Katherine "Kat" Ashley

Lettice Knollys, Countess of Leicester

George Talbot, 6. E. of Shrewsbury

Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury

Gilbert Talbot, 7. E. of Shrewsbury

Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Robert Sidney

Archbishop Matthew Parker

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Penelope Devereux, Lady Rich

Sir Christopher Hatton

Edward Courtenay, E. Devonshire

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Thomas Radcliffe, 3. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 4. Earl of Sussex

Robert Radcliffe, 5. Earl of Sussex

William Parr, Marquis of Northampton

Henry Wriothesley, 2. Southampton

Henry Wriothesley, 3. Southampton

Charles Neville, 6. E. Westmorland

Thomas Percy, 7. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 8. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 9. E. Nothumberland

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

Charles, Lord Howard of Effingham

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk

Henry Howard, 1. Earl of Northampton

Thomas Howard, 1. Earl of Suffolk

Henry Hastings, 3. E. of Huntingdon

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland

Francis Manners, 6th Earl of Rutland

Henry FitzAlan, 12. Earl of Arundel

Thomas, Earl Arundell of Wardour

Edward Somerset, E. of Worcester

William Davison

Sir Walter Mildmay

Sir Ralph Sadler

Sir Amyas Paulet

Gilbert Gifford

Anthony Browne, Viscount Montague

François, Duke of Alençon & Anjou

Mary, Queen of Scots

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell

Anthony Babington and the Babington Plot

John Knox

Philip II of Spain

The Spanish Armada, 1588

Sir Francis Drake

Sir John Hawkins

William Camden

Archbishop Whitgift

Martin Marprelate Controversy

John Penry (Martin Marprelate)

Richard Bancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury

John Dee, Alchemist

Philip Henslowe

Edward Alleyn

The Blackfriars Theatre

The Fortune Theatre

The Rose Theatre

The Swan Theatre

Children's Companies

The Admiral's Men

The Lord Chamberlain's Men

Citizen Comedy

The Isle of Dogs, 1597

Common Law

Court of Common Pleas

Court of King's Bench

Court of Star Chamber

Council of the North

Fleet Prison

Assize

Attainder

First Fruits & Tenths

Livery and Maintenance

Oyer and terminer

Praemunire

The Stuarts

King James I of England

Anne of Denmark

Henry, Prince of Wales

The Gunpowder Plot, 1605

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset

Arabella Stuart, Lady Lennox

William Alabaster

Bishop Hall

Bishop Thomas Morton

Archbishop William Laud

John Selden

Lucy Harington, Countess of Bedford

Henry Lawes

King Charles I

Queen Henrietta Maria

Long Parliament

Rump Parliament

Kentish Petition, 1642

Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford

John Digby, Earl of Bristol

George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax

Robert Devereux, 3rd E. of Essex

Robert Sidney, 2. E. of Leicester

Algernon Percy, E. of Northumberland

Henry Montagu, Earl of Manchester

Edward Montagu, 2. Earl of Manchester

The Restoration

King Charles II

King James II

Test Acts

Greenwich Palace

Hatfield House

Richmond Palace

Windsor Palace

Woodstock Manor

The Cinque Ports

Mermaid Tavern

Malmsey Wine

Great Fire of London, 1666

Merchant Taylors' School

Westminster School

The Sanctuary at Westminster

"Sanctuary"

Images:

Chart of the English Succession from William I through Henry VII

Medieval English Drama

London c1480, MS Royal 16

London, 1510, the earliest view in print

Map of England from Saxton's Descriptio Angliae, 1579

London in late 16th century

Location Map of Elizabethan London

Plan of the Bankside, Southwark, in Shakespeare's time

Detail of Norden's Map of the Bankside, 1593

Bull and Bear Baiting Rings from the Agas Map (1569-1590, pub. 1631)

Sketch of the Swan Theatre, c. 1596

Westminster in the Seventeenth Century, by Hollar

Visscher's View of London, 1616

Larger Visscher's View in Sections

c. 1690. View of London Churches, after the Great Fire

The Yard of the Tabard Inn from Thornbury, Old and New London

|

|