|

Henry had been so well worked upon by Jane Seymour and her friends

that he ardently wished to be rid of a woman with whom he was no longer in love, and who could not bear him the son he desired. He had already on several

occasions spoken of his marriage with Anne as invalid, and of his intention to proceed with another divorce. He had assured

Jane Seymour that his love for her was honourable, and had clearly shown that he intended to marry her. But, as usual, he had not courage to strike the

blow with his own hand; he was waiting for someone to take the responsibility of the deed.

Of course Cromwell might have helped to obtain a divorce; but he saw that it would be neither in his own nor in the king's

interest to proceed in this manner. To have applied for a divorce would have been to proclaim to the world that Henry, on entering the holy bonds of

matrimony, was careless whether there were impediments or not; it would have been to raise a very strong suspicion that the scruples of conscience he

had pleaded the first time were courtly enough to reappear whenever he wanted to be rid of a wife. Henry's reputation would have greatly suffered, and

as he knew this himself, although he chafed at his fetters, he dared not cast them off. A second reason—which more especially affected Cromwell—was

that Anne, if she were simply divorced, would still remain Marchioness of Pembroke, with a very considerable fortune, and with some devoted friends.

Rochford had gained experience, and showed no little ability, and he, acting with his sister, might form a party which

would be most hostile to the secretary.

Besides, a divorce could have been secured by Norfolk as easily as by Cromwell.

There would really have been no difficulty at all. Cranmer would not have dreamt of disobeying

the royal commands; he did in fact pronounce the marriage to be void. Of the other bishops one half were bitterly opposed to Anne, while most of those

whose promotion she had aided were supple courtiers who would do the king's bidding. Indeed, we hear of some zealous servant, who, perceiving what was

wanted, went on the 27th of April to consult Stokesley, the bishop of London, as to whether the marriage between the king and Anne was valid or not.

Stokesley, although he hated Anne and the Boleyns, was too cautious to offer an opinion. He said that he would reply to such a question only if it were

put by the king himself; and he added that, should the king intend to ask him, he would like to know beforehand the kind of answer that was desired.1

For all these reasons it was necessary that Anne Cromwell should be got rid of in a quicker and more violent way. Difficulties and dangers were to be

invented, that Cromwell might save the king from them. Anne was to be found guilty of such heinous offences that she would have no opportunity of

avenging her wrongs. Her friends were to be involved in her fall, and the event was to be associated with horrors that would strike the imagination of

the king and withdraw the attention of the public from the intrigue at the bottom of the scheme. Calamity was to be brought upon her, too, in a way that

would satisfy the hatred with which she was regarded by the nation, and take the ground away under the feet of the conspirators. Thus Cromwell, as he

afterwards told Chapuis, resolved to plot for the ruin of Anne.2

Whether Henry was at once informed that Anne was to be killed is not certain. Probably he was only told by Cromwell that he was menaced by grave dangers,

and that it would be necessary to appoint commissioners to hold special sessions at which offenders against him might be tried. On the 24th of April, in

accordance with these representations, the king signed a commission by which the Lord Chancellor Audeley, the Dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk, the Earl of Oxford, lord high chamberlain, the Earl of Westmoreland, the Earl of Wiltshire, lord privy seal, the Earl of Sussex, Lord Sandys, chamberlain of the household, Sir Thomas Cromwell, chief secretary, Sir William Fitzwilliam, treasurer, Sir William Paulet, comptroller of the household, and the nine judges or any four or more of them were empowered to make inquiry as to every kind of treason, by whomsoever committed, and to hold a special session to try the offenders.3 That this was virtually a death-warrant for Anne, Henry must have known, or at least suspected; but his conscience remained quiet: the deed would be done by others.

The commission was not made public; nor was it communicated to the persons to whom it was addressed. That would have been contrary to all the traditions

of the Tudor service. It was kept strictly secret; and only a few chosen instruments were to be employed until the case should be sufficiently prepared.

To make out a case against Anne was now the great object of Cromwell, and he began his task with characteristic energy.

The tacit understanding between Henry and Cromwell which led to the signing of the commission restored the secretary to his former influence.

* * * * *

Cromwell was thus in a position to devote himself to the work of collecting evidence against Anne. The old stories about her antenuptial misconduct would

not of course suffice. Even with regard to irregularities of which she had been accused after marriage there was a difficulty; for by the statute passed

in the autumn of 1534 any statement capable of being interpreted as a slander upon the king's issue might be accounted treason, so that people were rather

loath to repeat what they might have heard to Anne's discredit. Cromwell decided, therefore, to have her movements watched closely, in the hope that she

might be caught in some imprudence. As most of her servants were secretly her enemies, he did not doubt that some of them would gladly give information

against her, if they could do so without risking their own lives.

On the 23rd there had been an election to a place in the Order of the Garter, rendered vacant by the death of

Lord Abergavenny. Sir Nicholas Carew and

Lord Rochford had been candidates for it, and in ordinary circumstances the brother-in-law of the king would certainly have

carried the day. But it was Sir Nicholas, Anne's open enemy, who had been elected. This incident, although insignificant in itself, was of great service to

Cromwell, for those who disliked Anne began to think that it could not be very dangerous to speak against her, when she had not influence enough even to

obtain a favour for her brother. On the day after the election her opponents sent a triumphant and cheering message to Mary.4

It seems to have been Anne's own imprudence which gave Cromwell his first clue. She was exceedingly vain; and, like her daughter Elizabeth, who inherited

many of the qualities of her strange character, she delighted in the admiration of men, and fancied that every man who saw her was fascinated by her charms.

Her courtiers soon found out that the surest road to her favour was either to tell her that other men were in love with her, or to pretend that they were

in love with her themselves. She was extremely coarse, and lived at a most dissolute court; so that the flattery she asked for was offered in no very modest

terms. Lately, her health had been giving way, and her mirror had been reminding her that she was getting rather old and losing her good looks. This caused

her to crave more than ever for adulation; and her increased coquetry gave rise to scandalous stories, and provided Cromwell with the kind of charges he wanted.

On the 29th of April, at Mark Greenwich, Anne found a certain Mark Smeton, a groom of the chamber to Henry, and a player on the

lute, standing in the bow of the window of her chamber of presence. She went up to him, and, according to her own statement, asked him why he was so sad.

Smeton replied it was no matter; and she then said, "You may not look to have me speak to you as I should to a nobleman, because you be an inferior person."

"No, no," Smeton replied, "a look sufficeth me, and so fare-you-well."5

The conversation seems to have been overheard, and to have been reported by Cromwell's spies. Smeton's manner, or that of Anne, had excited suspicion; and

when, on the following day, the unhappy musician took his way to London, he was arrested at Stepney and rigorously examined.6 It is not known how

much Smeton confessed at this first examination. He may not have admitted that he had committed adultery with Anne; but he was no hero, and fear of the rack

or the hope of pardon probably led him to make statements by which she was seriously compromised and by which other persons were implicated. He was kept in

close confinement at a house in Stepney, but his arrest and examination were not immediately made known, for Cromwell wanted further evidence before striking

the blow.

Among the friends of Anne there was a young courtier named Sir Francis Weston, the son of Sir Richard Weston, under-treasurer of the

exchequer. He had first been a royal page, but had risen to the rank of groom of the privy chamber, and was now one of the gentlemen of it. For the last eight

years, by reason of his office, he had resided constantly at court, and he had obtained a good many grants and pensions. In May, 1530, he had married Anne, the

daughter and heiress of Sir Christopher Pykering; and having thus become a man of considerable property, he was created, at the coronation of Anne, a knight of

the Bath.

Another of Anne's friends was Henry Noreys, Henry also a gentleman of the king's chamber, and the keeper of his privy purse. Noreys

had been for many years a favourite attendant of Henry. He had at once sided with Anne when she had begun her struggle; and he had been among the foremost of

those who had worked the ruin of Wolsey. Ever since the death of the cardinal he had belonged to the little group of personal

adherents of the Boleyns. He had married a daughter of Lord Dacres of the South; but having been for some time a widower it had occurred to him that he would

please both Henry and Anne if he took as his second wife pretty Margaret Shelton, who, although she had lost her hold on Henry's caprice, had remained at court.

So a marriage had been arranged between him and Mistress Margaret. But of late he had become somewhat cold, and Anne attributed his estrangement to jealousy,

for she had observed that Sir Francis Weston had been paying rather marked attentions to her cousin. Accordingly, on the 23rd of April she had some private

talk with Sir Francis, and upbraided him for making love to Margaret and for not loving his wife. The young man, knowing how great was her appetite for flattery,

answered that he loved some one in her house more than either his wife or Margaret Shelton. Anne eagerly asked who it was, and he replied, "It is yourself." She

affected to be angry, and rebuked him for his boldness; but the reprimand cannot have been very terrible, for Weston continued his talk, and told her that Noreys

also came to her chamber more for her sake than for that of Madge, as Margaret Shelton was called.7

Finding all this very interesting, Anne took occasion to speak to Noreys, hoping perhaps that he would gratify her with the same kind of compliments as those

which had been paid to her by Weston. She asked him why he did not marry her cousin, to which he replied evasively that he would wait for some time. Displeased

by this cautious answer, Anne said he was waiting for dead men's shoes, for if aught came to the king but good, he would look to have her. Noreys, being older

and more experienced than Weston, understood how dangerous a game he was being made to play. He strongly protested that he dared not lift his eyes so high; if

he had any such thoughts, he would his head were cut off. Anne then taunted him with what Weston had told her. She could undo him if she would, she said. About

this they seem to have had some words, Noreys being evidently afraid that he might be drawn into a perilous position. Perhaps Anne herself began to feel uneasy,

for she ended the conversation by asking Noreys to contradict any rumours against her honour. This he consented to do, and on Sunday, the last day of April, he

told Anne's almoner that he would swear for the queen that she was a good woman.8 Cromwell apparently heard of this conversation, and concluded that

the time had almost come for making the case public. Henry was informed of what was about to be done, that he might be ready to play his part.

The following day being May Day, a tournament was held at Greenwich,

Henry Noreys and Lord Rochford being among the challengers. The king and Anne were present, and seemed

to be still on tolerable terms. When the tilting was over, Henry bade Anne farewell, and, as had lately become his custom, rode off towards London. On the way

he called Noreys to his side, and telling him he was suspected of having committed adultery with the queen, urged him to make full confession. Although the king

held out hopes of pardon, Noreys refused to say anything against Anne, and protested that his relations with her had been perfectly innocent. Henry then rode away,

and Noreys was immediately arrested, and kept, like Smeton, a close prisoner.9 He was taken to the Tower by Sir William Fitzwilliam,

who, it was afterwards asserted, tried hard to persuade him to confess that he was guilty. Whether, as was further stated, Noreys said anything that compromised

Anne is not known, but he certainly did not confess that he had committed adultery with her.10 Having left him at the Tower—to which Smeton had

been brought about the same time—Sir William Fitzwilliam went to Greenwich, where

the commissioners were to examine Anne herself.

That evening nothing further was done. Anne was treated with the outward respect due to a queen, but she knew that her enemies were working against her, and that

she was threatened by the greatest dangers. At ten o'clock at night she heard that Smeton was confined in the Tower, and shortly afterwards

it was reported to her that Noreys had been sent there too. Combining these facts with Henry's growing coldness to herself, and his

increasing affection for Jane Seymour, Anne began to fear that she would have to take the same way.11

She was absolutely without means of defence. Henry had gone to to be out of the way, and she could not bring her personal

influence to bear on him. The few friends she had were equally out of reach, most of them having gone with the king to London; so she could do nothing but await

her doom. Even flight was impossible, for had she been able to leave the palace and to go on board a ship—to elude the vigilance of the searchers and to

cross the sea—she would not have been safe. Neither Charles nor Francis would have afforded her an asylum; her flight would have been taken as a clear

proof of guilt, and she would have been given up in accordance with the treaties which forbade the various sovereigns to shelter one another's traitors.

So passed the night. On the following morning [May 2] Anne received a message requesting her to appear before the council. She obeyed, and was then told of the

powers given to the royal commissioners. She was also informed that she was suspected of having committed adultery with three different

persons—Smeton, Noreys, and a third whose name does not appear—and that the two former had already

confessed the crime. Her remonstrances and protestations had no effect.12 She subsequently described the behaviour of the commissioners as generally

rude. The Duke of Norfolk, who presided, would not listen to her defence;

Sir William Fitzwilliam seemed the whole time to be absent in mind;

Sir William Paulet alone treated her with courtesy.13

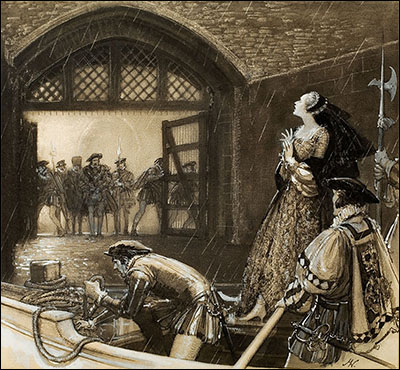

At the end of the interrogatories, the royal commissioners ordered Anne to be arrested, and she was kept in her apartment until the tide would serve to take her

to the Tower. At two o'clock her barge was in readiness, and in broad daylight, exposed to the gaze of the populace who had assembled on the banks or in boats

and barges, she was carried along the river to the traitors' gate.14 She was accompanied by the

Duke of Norfolk, Lord Oxford,

and Lord Sandys, with a detachment of the guard.

Lord Rochford had already been caught in the toils which had been woven for Anne's destruction. He was an able and energetic man,

strongly attached to his sister; and it was foreseen that in so dreadful an emergency he would, if left at large, do everything in his power to save her. So he

was arrested towards noon at Westminster, and taken to the Tower.15 Anne's friends were closely watched, but it was not thought necessary to interfere

with the liberty of Lord Wiltshire. He was a mean egotist and coward, and from motives of

prudence had always disapproved of his daughter's bold and violent courses. There was, therefore, no reason to fear that he would try to defend her.

At the Tower Anne was received by Sir William Kingston, the constable, of whom Chapuis had reported that he

was wholly devoted to Catherine and Mary. To his keeping she was handed over by the commissioners.

Up to this moment she seems to have maintained an appearance of firmness; but when the gates had shut behind the departing councillors, when she found herself

surrounded by the gloomy walls of the Tower, in the custody of the constable, her courage gave way. She realised the full horror of her situation, and as Kingston

beckoned to her to proceed, fearful visions of loathsome prison cells rose before her mind. She tremblingly asked Kingston whether he was leading her to a dungeon.

He reassured her, saying that she was to go to the lodging she had occupied before her coronation. This somewhat relieved her distress. "It is too good for me,"

she exclaimed. But, the tension of the last hour having been too much for her shattered nerves, she fell on her knees and burst into hysterical fits of laughter

and weeping.

When she calmed down she was taken to her apartment, where four gentlewomen under the superintendence of Lady Kingston had been deputed to wait on her. Suspecting

what had happened to her brother, she made a few anxious inquiries about him, and Kingston, who seems to have felt some pity for her,

merely answered that he had left Lord Rochford that morning at Whitehall. She asked that the eucharist might be exposed in a closet near her room, that she might

pray for mercy; and then she began to assert her innocence of the crimes with which she was charged. But these were matters to which Kingston would not listen, and

he went away, leaving her to the care of her female gaolers.16

The news of Anne's arrest and imprisonment ran like wildfire through the city. It was known that she was accused of having committed adultery with Noreys, or with

Noreys and Smeton, and that Lord Rochford and others were somehow involved in the

case, but as yet nothing was heard of the charge of incest. Rochford was said to have been arrested for having connived at his sister's evil deeds.17

The fate which had overtaken Anne excited little sympathy. Even among the Protestants, who formed at this time in England but a small class, there were some who

disliked her. The great majority of the people, detesting the changes of recent years, accused her and her family of having plunged England into danger, strife,

and misery in order to satisfy their own ambition and greed. The difficulties abroad and the consequent slackness of trade, the severity of the new laws and the

rigour with which they were enforced, were held to be due altogether to Anne's ascendancy; and it was expected that with her downfall there would be a total change

of policy, which would place England once more in a secure and prosperous condition.

But there was a man whom the tidings filled with dismay. For some months Cranmer had been ill at ease.

The ultra reformers, Anne's friends, had not been favoured since her influence had begun to decay; and the archbishop, who relied chiefly on them, had found himself

under a cloud.18 In the country he received a letter from Cromwell, informing him of the arrest of Anne and of the reasons for

it, and ordering him to proceed to Lambeth, there to await the king's pleasure, but not to present himself at court. He obeyed with a heavy heart, for such an order

from the secretary boded no good, and Cranmer was not the man to face danger calmly. Next morning, at Lambeth, he indited

a letter to the king, beseeching him not to visit the faults which might be found in the queen

on the Church she had helped to build up.

The archbishop had just finished writing when he received a message to appear before the council at Westminster. Such a message at such a time seemed even more ominous

than Cromwell's letter, but it was peremptory, and had to be obeyed. Cranmer took his barge, crossed the river, and went to the

Star Chamber, where he found the Lord Chancellor Audley, the Earls of

Oxford and Sussex, and Lord Sandys.

By the terms of the commission of the 24th of April they formed a quorum; and it is probable that they subjected Cranmer to an examination. But he seems to have been

either unable or unwilling to furnish fresh evidence against Anne. The commissioners acquainted him with the proof which they had, or pretended to have, of her guilt;

and the primate, cowed by the manner in which he was treated, declared himself satisfied with it. He returned to Lambeth, and there added a postscript to his letter,

saying he was exceedingly sorry such things could be proved against the queen.19

1. E. Chapuis to Charles V., April 29, 1536, Vienna Archives, P.C. 230, i. fol. 78: "Le frere de monsieur de

Montaguz me dit hier en disnant que avant hier que levesque de Londres avoit este interrogue si ce Roy pourroit habandonner la dicte concubyne et quil nen avoit point

voulu dire son adviz ne le diroit a personne du monde que au seul Roy et que avant de ce faire yl vouldroit bien espier la fantaisie dudict Roy vuillant innuyr que le

dict Roy pourroit laisser la dicte concubyne toutteffois connaissant linconstance et mutabilite de ce Roy il ne se vouldroit mectre en dangier de la dite concubyne.

Ledict evesque a este la principale cause et instrument du premier divorce dont de bon cueur il sen repent et de meilleur vouldroit poursuivre cestuy mesme a cause

que la dicte concubyne et toute sa race sont si habominablement lutheriens."

2. E. Chapuis to Charles V., June 6, 1536, Vienna Archives, P.C. 230, i. fol. 92: "Et que sur le deplesir et courroux quil avoit eu sur la responce que le Roy son

maistre mavoit donne le tiers jours de pasques il se meist a fantaisie et conspira le dict affaire . . ."

3. R.O. Baga de Segretis, Pouch VIII. Membranes 10 and 14.

4. E. Chapuis to Charles V., April 29, 1536, loc. cit.: "Le grand escuyer maistre Caro eust le jour Sainct George lordre de la jarettiere et fust subroge au

lieu vacant par la mort de monsieur de Burgain, qua este ung grand crevecueur pour le seigneur de Rocheffort que le poursuyvoit mais encoires plus que la concubyne

que na eust le credit le faire donner a son dict frere, et ne tiendra audict escuyer que la dicte concubyne quelque cousine quelle luy soit ne soit desarconnee et

ne cesse de conseiller maistresse Semel avec autres conspirateurs pour luy faire une venue et ny a point quatre jours que luy et certains de la chambre ont mande

dire a la princesse quelle feit bonne chiere et que briefvement sa contrepartie mectroit de leau au vin car ce Roy estoit desia tres tant tanne et ennuye de la

concubyne qui nestoit possible de plus."

5. Sir William Kingston to Cromwell, Cotton MSS., Otho C. x. fols. 224-26, printed in Singer's edition of

Cavendish's Life of Wolsey, p. 456.

6. Constantyne's Memorial to Cromwell, Archæologia, vol. xxiii. pp. 63-65; and Cronica del Rey Enrico otavo de Ingalaterra.

7. Sir W. Kingston to Cromwell, May 3, 1536, British Museum, Cotton MSS., Otho C. x fol. 225, printed by Singer, p. 451.

8. 2 Sir W. Kingston to Cromwell, May 3, 1536, loc. cit.

9 Constantyne to Cromwell, Archæologia, vol. xxiii. pp. 63-65; and Histoire de Anne de Boullant, etc.

10. Sir E. Baynton to Sir W. Fitzwilliam, British Museum, Cotton MSS., Otho C. x. fol. 209b.

11. Sir W. Kingston to Cromwell, British Museum, Cotton MSS., Otho C. x. fol. 224b.

12. Sir William Kingston to Cromwell, May 3, 1536, loc. cit.

13. Sir William Kingston to Cromwell, Cotton MSS., Otho C. x. fol. 224b.

14. E. Chapuis to Charles V., May 2, 1536, Vienna Archives, P.C. 230, i. fol. 80: "Laffaire . . . est venue beaulcop mieulx quasy que personne peust penser et a la

plus grande ignominie de la dicte concubyne laquelle par jugement et pugnicion de dieu a ete amenee de plein jour dois Grynuych a la tour de ceste ville de Londres

ou elle a este conduicte par le duc de Norphoch, les deux chambellan du Royaulme et de la chambre et luy a lon laisse tant seullement quatre femmes . . .";

Histoire de Anne de Boullant; Wriothesley's Chronicle of the Tudors, etc.

15. E. Chapuis to Charles V., May 2, 1536, loc. cit.: "Le frere de la dicte concubyne nomme Rocheffort a este aussy mis en la dicte tour mais plus de six

heures apres les aultres et trois ou quatre heures avant sa dicte seur . . ."; Wriothesley's Chronicle; and Cromwell to Gardiner and Wallop, May 14, 1536,

British Museum, Add. MSS. 25,144, fol. 160.

16. Kingston to Cromwell, May 3, 1536, loc. cit..

17. Roland Buckley to Sir Richard Buckley, May 2, 1536, R.O., Henry VIII., 28th, Bundle II.: "Sir ye shall untherstande that the queene is in the towere, the ierles

of Wyltshyre her father my lorde Rocheforde her brother, maister norres on of the king previe chamber, on maister Markes on of the kings preyve chamber, wyth divers

others soundry ladys. The causse of there committing there is of certen hie treson comytyde conscernyng there prynce, that is to saye that maister norres shuld have

a doe wyth the queyne and Marke and the other acsesari to the sayme . . ."; and E. Chapuis to Charles V., May 2, 1536, loc. cit.: "Le bruyt est que cest pour

adultere auquel elle a longuement continue avec ung joueur despinette de sa chambre lequel a este dois ce matin mis en ladicte tour, et maistre Norris le plus prive

et familier sommeiller de corps de ce Roy pour non avoir revele les affaires . . ."

18. Cranmer to Cromwell, April 22, 1536, R.O., Cranmer Letters, No. 45.

19. Cranmer to Henry VIII., May 3, 1536, British Museum, Cotton MSS., Otho C. x. fol. 225,

printed by Burnet, etc.

Source:

Friedmann, Paul. Anne Boleyn.

London: Macmillan and Co., 1884. 239-257.

Books for further study:

Ives, Eric. The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn.

Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

Starkey, David. Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII.

New York: Harper Perennial, 2004.

Warnicke, Retha M. The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Weir, Alison. The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn.

New York: Ballantine Books, 2010.

Weir, Alison. The Six Wives of Henry VIII.

New York: Grove Press, 1991.

| to Anne Boleyn

|

| to King Henry VIII

|

| to Luminarium Encyclopedia |

Site ©1996-2023 Anniina Jokinen. All rights reserved.

This page was created on May 2, 2012. Last updated May 2, 2023.

|